In the vast lexicon of Sanatan Dharm, the term ‘Varna,’ often misinterpreted as ‘caste,’ holds a far more profound significance. The essence of Varna is neither discriminatory nor restrictive; instead, it is a system that promotes self-discovery, societal organization, and personal growth.

The Four Varnas

The Varna system in Sanatan Dharm divides society into four major categories: Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and Shudras, each with distinctive traits and responsibilities.

Brahmins: The intellectuals, teachers, and scholars. As per Bhagwad Gita (18.42):

śhamo damas tapaḥ śhauchaṁ kṣhāntir ārjavam eva cha

jñānaṁ vijñānam āstikyaṁ brahma-karma svabhāva-jam

“Tranquility, restraint, austerity, purity, patience, integrity, knowledge, wisdom, and belief in a hereafter—these are the intrinsic qualities of work for Brahmins.”

Kshatriyas: The warriors, rulers, and administrators. As elucidated in Bhagwad Gita (18.43):

śhauryaṁ tejo dhṛitir dākṣhyaṁ yuddhe chāpy apalāyanam

dānam īśhvara-bhāvaśh cha kṣhātraṁ karma svabhāva-jam

“Valor, strength, fortitude, skill in weaponry, resolve never to retreat from battle, large-heartedness in charity, and leadership abilities, these are the natural qualities of work for Kshatriyas.”

Vaishyas: The merchants, agriculturists, and traders. As described in Bhagwad Gita (18.44 – 1st line):

kṛiṣhi-gau-rakṣhya-vāṇijyaṁ vaiśhya-karma svabhāva-jam

“Agriculture, dairy farming, and commerce are the natural works for those with the qualities of Vaishyas.

Shudras: Those who serve the other 3 Varnas. As described in Bhagwad Gita (18.44 – 2nd line):

paricharyātmakaṁ karma śhūdrasyāpi svabhāva-jam

Serving through work is the natural duty for those with the qualities of Shudras.

The Manusmriti (Verse 10.4) confirms this classification:

brāhmaṇaḥ kṣatriyo vaiśyastayo varṇā dvijātayaḥ

caturtha ekajātistu śūdro nāsti tu pañcamaḥ

“The Brāhmaṇa, the Kṣatriya, and the Vaiśya are the three twice-born varnas; the fourth is the one varna, Śūdra; there is no fifth.”

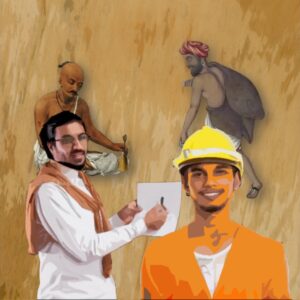

However, these Varnas do not denote hereditary castes but represent fluid classifications based on inherent qualities and deeds.

Varna and Deeds: Not Hereditary but Acquired

The Varna system is not a rigid, birth-based stratification as it’s often misconstrued. It classifies individuals based on their inherent qualities (Gunas) and actions (Karma), not birth. The Manusmriti (Verse 10.65) affirms this principle:

The Varna system is not a rigid, birth-based stratification as it’s often misconstrued. It classifies individuals based on their inherent qualities (Gunas) and actions (Karma), not birth. The Manusmriti (Verse 10.65) affirms this principle:

śūdro brāhmaṇatāmeti brāhmaṇaścaiti śūdratām |

kṣatriyāj jātamevaṃ tu vidyād vaiśyāt tathaiva ca || 65 ||

“The Śūdra attains the position of the Brāhmaṇa, and the Brāhmaṇa sinks to the position of the Śūdra; the same should be understood to be the case with the offspring of the Kṣatriya or of the Vaiśya.”

The Role of Deeds in Determining Varna

Bhagavad Gita (18.55) provides further insight into this, emphasizing the critical role of performing one’s duties to attain perfection:

sve sve karmaṇyabhirataḥ saṁsiddhiṁ labhate naraḥ

svakarmanirataḥ siddhiṁ yathā vindati tachchhṛiṇu

“Each person attains perfection by dedicating themselves to their natural duties. Now hear how a person attains perfection by engaging in their natural duties.”

It is clear that the Varna system, as envisaged in Sanatan Dharm, is a profound and flexible social structure designed to cater to individual predispositions and talents, focusing more on personal qualities and deeds rather than birth.

The Flexibility of the Varna System

The dynamism of the Varna system is evident from the fact that it can be changed during a person’s life through actions. The Bhagwad Gita (Verse 18.55) states, “By fulfilling their duties, born of their innate qualities, human beings can attain perfection.” This verse elucidates the adaptability and fluidity of the Varna system, signifying that the Varna of an individual can evolve based on one’s actions and qualities.

The dynamism of the Varna system is evident from the fact that it can be changed during a person’s life through actions. The Bhagwad Gita (Verse 18.55) states, “By fulfilling their duties, born of their innate qualities, human beings can attain perfection.” This verse elucidates the adaptability and fluidity of the Varna system, signifying that the Varna of an individual can evolve based on one’s actions and qualities.

Misinterpretations and Misconceptions

The rigid interpretation of the Varna system, with no scope for upward mobility, is a more modern concept and is largely a result of the willful erroneous translation and interpretation of Hindu scriptures. A primary culprit in this misrepresentation was the German philologist and Orientalist Friedrich Max Muller.

While Max Muller played a significant role in introducing the Western world to the vast corpus of Indian scriptures, his translations, particularly concerning the Varna system, have been widely criticized for injecting colonial and racial biases. His translation, influenced by the prevalent social stratification in Victorian England, cast the Varna system as a rigid, birth-based system, which was contradictory to the fluid, qualities, and deeds-based categorization envisioned in the original texts.

To fully comprehend the wisdom of Sanatan Dharm, it is critical to understand the Varna system’s true essence and intent. An unbiased interpretation reveals a profound social structure that values individual qualities and contributions, providing a pathway for everyone to attain perfection through their unique path of action.

The Jāti System in Sanatan Dharma: A Fluid Classification Rooted in Occupation

The concept of Jāti in Sanatan Dharma, often translated as ‘caste’, traces its roots to the Sanskrit word ‘जाति’ (Jāti), derived from ‘जात्’ (Jāt), which means ‘born’ or, in a broader sense, ‘born in.’ Rather than denoting a rigid hierarchy, the Jāti system provides a flexible, occupation-based classification much akin to the concept of a ‘clan’ in English. This system has practical implications, largely influenced by the occupational nature of the family one is born into, and has been misinterpreted and misrepresented over time, often for political or ideological reasons.

Jāti: A Socio-occupational Classification

The Jāti system essentially pertains to the occupation or profession of a family or community. A child born into a goldsmith’s family, for instance, would naturally acquire the skills of melting, casting, and carving gold from a young age. Such skill inheritance leads to the child’s outperformance in the goldsmithing art, compared to children from other Jātis.

It’s critical to understand that the Jāti system is neither rigid nor immutable. New Jātis can emerge, reflecting changes in the job market or societal structure. For example, the British India era saw the rise of the Kanungo Jāti, supervisors of Patwaris (village registrars or clerks in the Indian system), where ‘Kanungo’ symbolizes ‘the knower of laws’. As society evolves, it’s plausible that a new Jāti such as ‘Sanganakagya’ (a term translating to ‘Knower of Computers’) might arise, reflecting the prevalence of software engineers in modern society.

The Fluidity and Mobility within the Jāti System

The Jāti system provides a broad framework, not a constraining straitjacket. There’s significant fluidity in this system, as seen in how individuals across generations have chosen professions outside of their family occupations.

While it’s common to see children pursuing professions similar to their parents – like a doctor’s child becoming a doctor or a lawyer’s child a lawyer – there are countless instances of individuals breaking this trend. A doctor’s son might choose to become an actor, or a lawyer’s son may develop a passion for astrophysics. The Jāti (often denoted by one’s surname) does not dictate a person’s destiny or occupational choice.

Misinterpretations and Misrepresentations of the Jāti System

Contrary to popular belief and the numerous narratives peddled by Western Indologists and intellectuals, the Jāti system is not a confining structure designed to imprison individuals within certain occupations. It’s a flexible system allowing for occupational mobility and individual choice.

Notable figures in history demonstrate this fluidity. Gautam Buddha, born into royalty, chose a life of asceticism. Mahatma Gandhi, with a surname denoting skill in perfumery, is globally renowned not as a perfume maker but as a barrister-turned-freedom fighter.

Social Stratification in Victorian England: A Detailed Examination

Social stratification in Colonial England that peaked during the Victorian era (1837-1901) was markedly hierarchical, rigid, and complex. A social class system, largely based on birth, wealth, and occupation, dominated society and dictated one’s life opportunities. This system played a crucial role in shaping social relationships, economic conditions, and cultural norms.

The Aristocracy

At the top of Victorian England’s social hierarchy was the aristocracy, comprising the monarchy, nobles, dukes, earls, viscounts, barons, and other titled individuals. The aristocracy’s privileges stemmed primarily from hereditary titles and land ownership. This group made up a very small percentage of the population but held substantial influence in the political, social, and economic spheres.

The Aristocracy was further divided into the upper and lower aristocracy. The upper aristocracy included the royal family and the nobility, who were typically landowners with significant wealth. The lower aristocracy consisted of individuals with hereditary titles but had lesser landholdings and financial resources.

The Working Class

The majority of the Victorian population belonged to the working class, individuals employed in manual labor. This group included factory workers, miners, servants, farm laborers, and other manual laborers. Their work conditions were often harsh, with long hours, low pay, and minimal security.

The working class was divided into skilled, semi-skilled, and unskilled laborers. Skilled workers, such as artisans or craftsmen, had specific trades and could earn a decent living. Semi-skilled and unskilled laborers, however, often lived in poverty and faced challenging living conditions.

The Underclass

Beneath the working class was the underclass, comprised of the poor and destitute who struggled for daily survival. This group included beggars, vagrants, prostitutes, and criminals. They were generally unemployed or employed in low-paying, unstable jobs.

So, we can see clearly that England’s social stratification was a well-defined and rigid class system structured around birth, wealth, and occupation. It shaped social norms, life opportunities, and interpersonal relationships during the era. The upward mobility was a big zero and still exists in a somewhat diluted form.

So, what is Caste, then?

The English word “caste” was derived from the Portuguese term “casta,” meaning “race” or “lineage,” and can also be translated as “class of people” or “breed.” It referred to a fixed, hereditary system of social stratification. British colonizers loved the word. They found the concept of a social hierarchy similar to their own. This appealed to their English sensibilities, which were grounded in a well-defined class system back home.

Thus, the British, as part of their strategy of governance, codified and rigidified the fluid and complex social structures they encountered in India, simplifying them into a hierarchical system that could be easily managed and manipulated. This facilitated the British imperial policy of “divide and rule”, as it emphasized and institutionalized divisions within Indian society.

How Varna Became Caste

The imposition of the rigid British interpretation of “caste” upon the fluid Vedic Varna system had significant and lasting impacts on Indian society. It effectively hardened what was previously a more flexible structure, pushing individuals into rigid social and occupational roles based on their birth and fostering deep-seated social divisions that persist to this day.

- Loss of Social Mobility: The Vedic Varna system allowed for high social mobility, as it was rooted in individual abilities and qualities rather than birth. The British, however, rigidified these roles based on their understanding of caste as a hereditary, immutable class. This led to a loss of social mobility, with individuals trapped in the social roles assigned by their birth.

- Division and Discrimination: The British colonial government deepened the divisions between different castes, using them to divide and rule India. This led to increased discrimination and social tension between different social groups, many of which persist today.

- Distortion of Social Identity: The colonial interpretation of caste led to the distortion and oversimplification of India’s diverse social identities. Many diverse and complex social groups were lumped together under a single caste label, losing their unique identities and practices.

- Entrenchment of Caste Hierarchies: The colonial administration often favored certain castes over others for jobs and opportunities, entrenching social hierarchies and perpetuating social inequality. The effects of these policies continue to affect Indian society, with certain castes facing significant social and economic disadvantages.

- Creation of Caste Consciousness: Prior to British rule, individuals were conscious of their varna or jati, but the notion of a pan-Indian caste identity didn’t exist. The British classification created a consciousness about one’s caste on a pan-Indian level.

The imposition of the British understanding of “caste” on the Vedic Varna system created deep divisions and inequalities within Indian society that continue to persist. It created a rigid, hierarchical system of social stratification that was based on birth rather than individual qualities and abilities, significantly affecting the social dynamics of Indians not just in India but the Indian diaspora living in Western countries. The West still seeks to divide Indians based on “caste.” One such example is the caste-based Bill SB-403 in California. But that is a topic for another day.